-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

The Marine Mammal Center accurately reports that California sea lions (Zalophus californianus) are known for their intelligence,

playfulness, and noisy barking.

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

Western Grebe

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

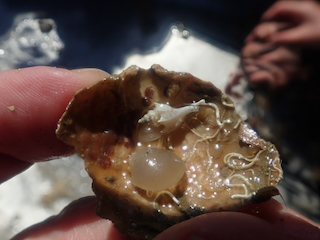

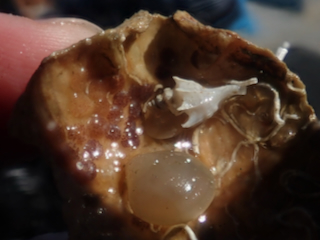

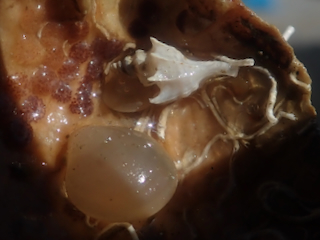

Crossota californica (California frog snail) with a large hermit crab inside. I am not sure what it was doing on the beach.

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

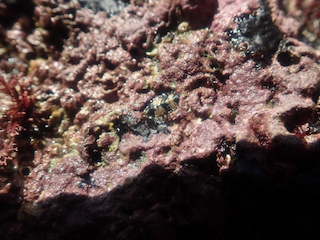

I had help by Bio 317 chiton specialist, Jennifer, finding tiny chitons that I have been studying

at the Two Harbors Campground, and other localities on multiple Channel Islands. I am working on a new species description, separating this Channel Islands endemic species

from a more northern species I described from the Central Coast of California, now as Cyanoplax caverna (sea cave brooding chiton; formerly placed in genus. Lepidochitona).

|

Unlike the central California sea cave brooder, which is one of two known hermaphroditic chiton species,

and capable of regular self-fertilization, the Channel Islands species has separate sexes, and probably is like other chitons, dependent on sexual cross-fertilization. Both species are

brooders, which means the mother broods the fertilized embryos along both sides of the foot, normally for about 10-12 days, at which point the late-stage trochophore

larvae that hatch out of the egg covering and are capable of crawling away (see Source).

|

To crawl away from your mother is relatively uncommon in chiton species, with only about five percent

of global chiton species, scattered with respect to phylogeny. There are are no clades of brooders. More normally, chiton females free spawn eggs or and males spawn sperm,

and after the gametes are externally fertilized, the result is a nonfeeding planktonic trochophore larva. The larva will hatch after only about a day,

spend another week of drifting in the plankton, soon getting a pair of eyespots and then a creeping foot, and after a week or so will settle given appropriate environmental cues and begin crawling

on hard substrate, metamorphosing soon after. In contrast, brooded embryos develop to the late crawling stage inside their brooded egg capsules, and they can at least potentially crawl away when they

do eventually hatch. There are consequences. To remain in the vicinity of

their mother, their siblings, and other relatives promotes inbreeding.

- Eernisse in Biological Bulletin

|

-

|

-

|

This presumed female was the largest Cyanoplax n.sp. Eernisse MS we found, and it was the only one we found

brooding embryos, which (as in their northern relative, C. caverna) were an attractive forest green in color.

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

Gobiesox rhessodon (California clingfish) brooding its guarding its embryos on the shell of a

clam, Semele decisa (clipped semele).

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

A student found this juvenile Cyanoplax hartwegii (Hartweg's chiton) on the underside of an intertidal

small rock. Like the two species of Cyanoplax discussed above, it is different from other Cyanoplax species in having irregular warty pustules on the lateral margins

of its shell plates. However, C. hartwegii gets much larger, has more gills on each side of its foot, can be distinguished by its DNA sequences, and is more typical

for chitons in reproducing as a free spawner, not brooding as those discussed above.

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

Snorkeling in Two Harbors, I saw the most gigantic black sea hares, larger than any that I can recall

seeing. Our black sea hare (Aplysia vaccaria) holds the record for the gastropod mollusk with the greatest body wet weight. According to Google's AI, it can

reach 75 cm (29 in) in length.

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

Centrostephanus coronatus (crowned urchin) is a black sea urchin that feeds nocturnally, unlike

purple or red sea urchins. This and its habit of seeking refuge during daylight hours helps protect it from being eaten by carnivorous fishes, especially large California sheephead,

Bodianus pulcher.

|

-

|

I found a live clam, just sitting out in the open.

|

This clam belongs to the species-rich and often confusing family of clams, Veneridae. Speaking confidently on behalf of

the community of all California malacologists, this one is a popular one: Chione californiensis (California venus clam).

|

Tegula aureotincta

|

Pteropurpura trialata

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

This is called Bird Rock for good reason.

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

In the background is Ship Rock.

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

Sometimes when the biological dredge returns nearly empty from more than 100 m depth,

there are still some interesting species.

|

There were several presumed salps, perhaps picked up on the ascent of the dredge.

|

-

|

A muricid (Muricidae) neogastropod only about 1 cm long, identified by me as Boreotrophon sp. but

Roger Clark (thanks!) helped me with this species identification: Boreotrophon avalonensis Dall, 1902. The several named species of this genus accepted as valid in southern California all

look quite similar to me, but click on Source to compare Dall's original description. - Source

|

The way B. avalonensis was adjacent to these juvenile brachiopods, Laqueus californianus, I thought

the snail might be feeding on them. I found no indication of any bore holes in these brachiopods. I was also interested because there seemed to be some sort of egg cases

nearby, that I am investigating further. Could they be from this snail?

|

-

|

Megasurcula stearnsiana (Raymond, 1906) was formerly grouped in a huge neogastropod family (Turridae, the turrids) with many genera and species.

Now it is still in the same superfamily, Conoidea, but Turridae has only 25 accepted genera, and Megasurcula belongs to Pseudomelatomidae, one of

55 accepted genera in this family.

|

Within its genus, Megasurcula stearnsiana can be found together on offshore sandy bottoms in southern California with the only

other member of this genus, the larger M. carpenteriana (Gabb, 1865). The latter species was designated as the type species for the genus.

|

-

|

This deep-water limpet belonging to the family, Lepetidae, is Iothia lindbergi, named by the late Dr. James McLean (see Source) to

honor the worldwide limpet expert, Dr. David R. Lindberg, who also happens to have been my grad school pal at UC Santa Cruz. He taught me so many cool things about limpets.

- Source

|

On the same small rock as the I. lindbergi was a chiton about 4 mm long that I have already

been investigating, belonging to the genus Leptochiton. It was one of two specimens found, the other even smaller.

|

-

|

A huge thanks to Dr. Leslie Harris, worm curator at the Natural History of L.A. Co., for first

identifying this beautiful polychaete to the rarely-seen-live family, Acoetidae, and after consulting the well-known indispensible Hartman's Atlas guide to polychaete identification,

she concluded that it could be either Acoetes pacificus (formerly as Panthalis pacificus) or Polyodontes panamensis, depending on whether the superior neurochaetae have

long hirsute tips (as in Polyodontes) or have tips that resemble a paint brush (as in Acoetes). All of the following except for this one

were later taken in my lab on the same day.

|

-

|

-

|

Acoetidae is one of six families in the polychaete order Phyllodocida, suborder Aphroditiformia, which

includes scale worms (Polynoidae) and sea mouses (Aphroditidae).

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

Under Construction!

Under Construction! Under Construction!

Under Construction!