-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

Gymnonereis crosslandi is a polychaete (segmented worms with many chaetae) of the family Nereidae.

Nereids are often omnivores, with some mainly predatory on

other worms, and this one from muddy habitats should be easily recognized by its parallel pair of golden pigment lines along the body.

Help in identification was kindly provided by worm expert, Dr. Leslie Harris.

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

From our 2017 cruise off San Pedro (we have seen it several times since!): Codium hubbsii

is typically subtidal and prostrate, meaning I assume it spreads out on the substrate. It is not especially closely related to the similar appearing, but more northern and

intertidal, C. setchellii. The latter is more irregular and tightly adherent to the substrate, usually in sandy areas, whereas C. hubbsii tends to be approximately

circular, with loose margins (2017 ID and details: Kathy Ann Miller).

|

Tentative: Lophopanopeus bellus (blackclaw crab). This crab has a variable color and pattern, from purple and orange to brown,

but nearly always has quite dark claw tips. Its legs are not as hairy and the claws are not as bumpy as the lumpy rubble crab (see below).

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

In back: Ophiodermella inermis; in front: Maxwellia santarosana

|

-

|

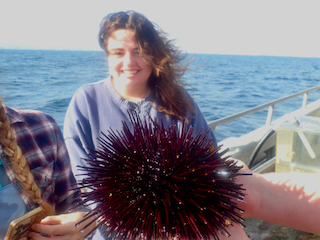

Red urchins (Mesocentrotus franciscanus) even larger than this one, specifically off Vancouver Island

in British Columbia, have been estimated to be about 200 years old. Source: Alaska Dept. Fish & Game

|

-

|

-

|

A venus clam, Globivenus fordii, seems to be fairly rare on the southern California mainland, and is

fairly rare in general, but is somewhat

more common off Catalina Island. There was an interesting paper on venus clam relationships that included some species of this genus (but not G. fordii) by

Isabella Kappner and R. Bieler (2006;

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution/i> 40(2): 317-331).

|

Tentative: juvenile Barbarofusus sp. (help with identification by P. LaFollete)

|

-

|

-

|

Lancelets are very interesting to zoologists as the only living representatives of an entirely separate

subphylym of our phylum, Chordata, known as Cephalochordata. This is one of three chordate subphyla, along with Urochordata (the tunicates), and our own chordate subphylum, Vertebrata.

It is interesting that Branchiostoma californiense Andrews, 1893 is reported to be the only

species of lancelet living

along the western coast of the Americas between about Monterey, California and Panama. There are about 22 other accepted species of this genus worldwide (according to the WoRMS

database),

plus there are two other lancelet genera with seven total other species, so 30 total species of lancelets. These are all in the same family and class within Cephalochordata.

It is remarkable to have only 30 living species in

a group that is known to extend back to the Cambrian period. How has it avoided becoming extinct with so few species? Still, it is unusual for any marine species

to be so wide ranging between central California and Panama, so maybe this single species is actually a cryptic species complex with more than one species.

No one has yet compared DNA sequences of B. californiense along throughout its Eastern Pacific range. Its type locality is nearby San Diego, California,

so it is likely that this particular lancelet is indeed Brachiostoma californiense.

|

-

|

-

|

Tentative genus: Harfordia (species still under investigation)

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

Paraxanthias taylori (lumpy rubble crab) - note the shiny bumps on the claws,

very hairly legs, and brownish claw tips.

|

-

|

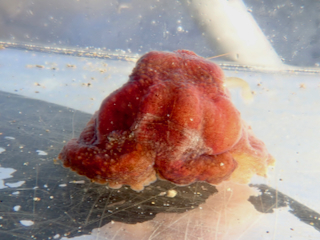

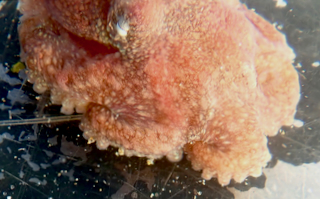

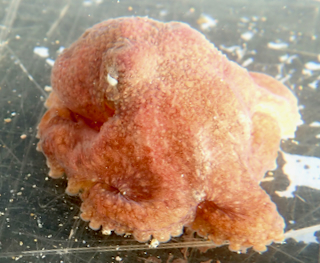

Like other octopus species, the red octopus (Octopus rubescens is quite clever and is a

master of disguises, here perhaps attempting to resemble a rock covered with tunicates.

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

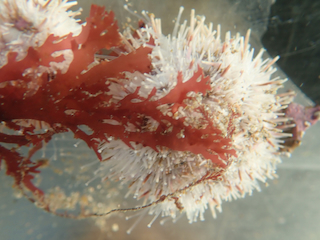

Ophiopteris papillosa (flat-spined brittle star)

|

-

|

Octopus rubescens females are known to come to the intertidal to lay and protect their eggs,

with juveniles emerging about six to eight weeks later, after which the female dies at about two years old. The male has already died after mating. One study that used

remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) found that O. rubescens was the most commonly found animal along the continental shelf of Monterey Bay, California, at depths of over

180 m (600 ft.), so they must reproduce a deeper than intertidal depths as well. Source: Monterey

Bay Aquarium

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

Snapping shrimps apparently compete with sperm and beluga whales for the loudest animals in the sea,

all those popping sounds you hear underwater while snorkeling or scuba diving. In fact, they are responsible for all that noise one hears in shallow water hydrophone recordings.

They can snap a cavitation bubble to generate an acoustic blast up to about 4 cm from its

oversized claw that can kill a small fish. I observed this one, Alpheus clamator (twistclaw pistol shrimp).

Source: Wikipedia article on the snapping shrimp family, Alpheidae

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

Lytechinus pictus (white urchin)

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

Under Construction!

Under Construction! Under Construction!

Under Construction!